Electronic Musician

December, 1996

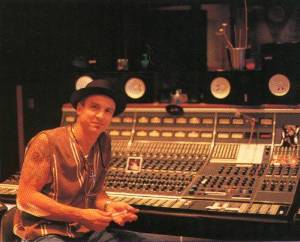

Sample some tasty guitar and vocal recording recipes that producer

Neil Giraldo and his wife, Pat Benatar, cook up in Spyder's Soul Kitchen.

Married to the Music

By Greg Pedersen

Neil Giraldo cooks up hits with wife, Pat Benatar, in the Soul Kitchen.

Although Neil Giraldo doesn't sing for his supper, he shares plenty of meals and a

successful recording career with a woman who does. Giraldo is married to Pat

Benatar, the four-time Grammy winner whose vocal prowess satiated the

public's hunger for rock candy in the 1980s with AOR smashes such as

"Love Is a Battlefield," "Hit Me with Your Best Shot," and "Promises in the

Dark." Giraldo has played an integral role in Benatar's career since her 1980

break-through album, Crimes of Passion, tackling the duties of producer,

guitarist, songwriter, and musical director.

In 1988, the dynamic duo began recording in their state-of-the-art home

studio, Spyder's Soul Kitchen, producing the major-label releases True Love

and Wide Awake in Dreamland. Benatar fans will be happy to know that the

latest offering from the Kitchen, Innamorata, is a focused, emotionally rich

work that marks a return to the guitar-driven pop of the singer's glory years.

After basking in the glow of arena lights and kicking some major booty

onstage (at the Northern California stop on Benatar's summer tour opening

for Steve Miller), Giraldo agreed to share some of his production secrets with

EM readers. Here's what went down.

You weren't credited as a producer on the first few Benatar albums, but

there have always been whispers that you had a substantial role in their

creation.

I really started producing during Crimes of Passion, even though I didn't get

credit. On Pat's first record, In the Heat of the Night, I was more of an

arranger. I would say stuff like, "I don't like the snare tone" or "The backbeat

feels wrong," but I wasn't sophisticated enough to know exactly how to fix a

problem.

One day, while I was still composing songs for Crimes of Passion,

[producer] Keith Olsen gave me the keys to his Porsche because he knew I

liked to write while driving. I drove around for a while, and when I came

back, Pat was crying. We were tracking the first song for the record, which

was probably "Hell Is for Children," and Keith said, "I don't know what to

do; she can't sing this part." I went into the control room, set up a better

headphone mix, talked her through the song a little bit, and got the vocal

happening. That's basically when I took over the production chores.

It seems you understand the fragile nature of singers. Does that

empathy help you capture a great vocal performance?

How you get a great performance has a lot to do with the kind of

environment you create. Emotion is a very important thing. If you knock

emotion out of people, you take the inspiration right out of them, too. What I

try to do is push positive reinforcement on everybody. It's like when you tell

your spouse, "You look great tonight." Ideally, that kind of comment should

make someone feel good. It's exactly the same way in the studio.

Did working with guitarist-producer Rick Derringer in his band help

you develop your ideas about record production?

No. Actually, I learned from Rick's approach what not to do. I didn't care for

the way Rick treated people in the studio. Technically, Rick knew what he

was doing, but he would say the wrong things to the musicians at the wrong

time. Also, his focus was as a guitar player whereas I always listen to the

entire arrangement and have opinions on everyone's performance. I'm

sensitive to the drum groove and the bass tones, not just the guitar parts.

After working together and being married so long, do you and Pat have

an ESP-type relationship in the studio?

Sometimes, she'll sing a couple of tracks, and I'll comp them and say, "That's

a pretty good vocal performance." She'll say, "Pretty good?" I'll answer,

"Yeah, I think it's really good," and as soon as I say that, she'll go in and sing

another take. It works every time. She always knows what I'm thinking; it's

almost like she corrects the performance before I say anything. We've been

together twenty years, so just my tone of voice will tell her that I think she

can take it one step further. But her takes are never bad.

What are some of the initial tasks involved in recording Pat's vocals?

Typically, I'll do the headphone mix and make sure that I get a good balance

of instruments for her. Then I let her run through the song once. I always

compress her voice, usually with an old Neve stereo unit - I forget the

number, but it's one of the vertical models - set to a real gentle, fast release

time. In addition, I insert a limiter at the end of the signal chain so that none

of the peaks take us too far into the red, causing unnecessary tape saturation.

Sometimes there will be a situation when everything is set perfectly to catch

all the peaks and things still sizzle a bit. That happened when we recorded

Pat's vocals on "Fire and Ice." You can hear some slight distortion on the

record.

Did you go through a trial-and-error process to find the perfect mic for

Pat's voice?

Oh, yeah! I tended to use the Neumann U 67 tube mics a lot, but they had

certain quirks that really bummed me out. For example, when we'd go to fix a

couple of vocal things, the punched-in lines would always sound a little

different than the original vocal track. The tonal variations occurred because

the mic's tone would change after the tube warmed tip and then it would

fluctuate again as the tube started to "tire out" from hours of rise. So

sometimes I'd put up an AKG C 414 to capture a more consistent tone.

Pat will also sing into a Shure SM58 mic as she runs through a song, and

occasionally we'll rise those scratch tracks in the final mix. Often, when she is

talking into the mic before we start recording, I'll notice that her voice sounds

too bright or has too much presence, and I'll change the mic before she even

starts singing. You just have to listen and use whatever mic works on a given

day for a given track.

What about the mix? Do you have any favorite tricks to enhance her

voice?

I always use an EMT 250 because it's the most beautiful sounding digital

reverb, and it sounds absolutely great oil her voice. I set a 120-millisecond

predelay, so when she sings, you don't hear the reverb immediately. The

reverb appears right after each word, kind of like a cloud.

Another trick I rise is doubling the vocal electronically with a stereo delay. I

typically set the delay time to 35 milliseconds and compress the input signal.

It's subtle, but the sound is brilliant. if you do it right, the vocal effect is sort

of like the one John Lennon's "Instant Karma."

You've recorded guitar tracks in some pretty famous studios with

bigwigs like producer Keith Olsen. Let's discuss some practical

applications to capturing a great guitar tone.

Well, a Shure SM57 is a great mic for recording guitars. An AKG C 414 is

good, too, because it adds a certain brilliance to the sound. Placement-wise, I

stick the microphone right up against the speaker cabinet's grille cloth. Then,

I play the guitar and listen through headphones while I move the mic around

to find the spot where everything sounds good. Sometimes I'll tilt the mic

off-axis to the speaker by 45 degrees to take a bit of the scratchiness away.

For miking acoustics, I typically use a Neumann KM 184 tilted towards the

15th fret.

It also helps that I've got an old Neve 8068 console. The Neve definitely

colors the sounds that go through it, and I like that. There's not a better

sound than a vocal or a guitar going through a Neve. That sound, combined

with the right mic, usually eliminates the need for tons of EQ.

Another major element of my guitar sound is a Fairchild Model 670 stereo

tube compressor. I have a little trick where I will not use the mic preamps on

the Neve to get the maximum signal level to tape. What I'll do is set the Neve

preamps to about half and then make up the gain with the Fairchild. That

method of gain staging ensures the guitar signal is getting the maximum tonal

benefits of the Fairchild's tubes-which is the way to go if you're going to

spend the money to buy the 22 tubes that thing uses!

You obviously prefer an extremely close-miked guitar tone rather than

placing mics to also capture some room ambiance.

Yeah. I remember walking into a session where the engineer placed one mic

on the speaker grille and another mic about three feet back. I looked at him

right away and said, "The sound is never going to be completely in sync. It'll

sound tubby."

Do you find yourself twisting EQ knobs to dial in the guitar tones

you're after?

I never EQ my guitars to tape during recording. I'll only add EQ during the

mix, and that's often limited to a few boosts at 10 kHz and 700 Hz to get

some extra chunk. I usually like to keep sounds as flat as possible. I've

worked with engineers who EQ everything, and it can get out of hand. I

mean, if the drains are heavily EQ'd, you have to EQ the guitars so their

sound matches the intensity of the drum sounds. And then you have to EQ

the vocals heavily so that they can stand out from the guitars, and so on. It's

a mess.

Do your demos ever sound better than the studio tracks?

Well, I have recorded demos that turned out to be masters. "Let's Stay

Together" [from the album Wide Awake in Dreamland] is a good example.

The song was a demo that only lasted about a minute, and we had to

construct the final track by looping the verses and choruses and dropping

them onto the master reel. That was a real headache!

I have found that if a demo just kicks the heck out of the "real" track, it's

important to maintain the demo's instrumentation on the final version -

especially if you plan to fly in tracks from the demo to the master reel. I

mean, do not change one instrument from the arrangement on the demo. If

you do, it will permanently upset the balance of the other instruments, and

you'll lose the sound and vibe that made the demo so special.

How much do your songs evolve from the demos to the final recorded

versions?

Let me think of a few examples. Well, "All Fired Up" [from the album Wide

Awake in Dreamland] used to start with just guitar. But when we started

recording the studio version, I was kind of bummed because we weren't

getting the track together. So I asked the drummer, "What are you doing?"

We got into an argument about the parts, and then I just broke into this

groove, and that's how the song's intro came about. The breakdown in the

middle section wasn't planned, either. It was basically a magical moment that

just happened-it wasn't on the demo and it wasn't supposed to be there.

That just goes to show you can't ignore the importance of "accidents" in the

studio. For example, the drum machine introduction to "Love Is a Battlefield"

[from Get Nervous] was a mistake. I accidentally hit something on the Linn

that made a 6-bar phrase instead of the 8-bar phrase I wanted. But the 6-bar

phrase had a nice rhythmic turnaround that worked great.

A unique groove can definitely make a pop song come alive. If you notice, on

all those big records we did, the songs have a real strong, identifiable rhythm.

I love rhythm; I am a frustrated drummer!

After all the hard work you've done during tracking. how do you

preserve the feel of the song when it comes time to mix?

Well, getting the right perspective is important. So as soon as you record your

last overdub, do a tough mix right away to document a good vibe for the

track. If you wait two weeks or so to mix, You'll never capture the song. It's

critical to get some kind of mix down while you're still building the track and

the song is a living thing.

Your motto as a producer seems to be "Keep it simple." Is that the

ideal you would like to impart to readers of Electronic Musician?

Well, the records that [producer] Trevor Horn makes with Seal are really

complex. There's a lot of stuff going on and eve thing sounds fantastic. He

also spends two years and two million dollars making an album. EM readers

may eventually want to get to that stage, but I recommend keeping your

productions as organic as possible because, many times, that's where you'll

capture the magic.

Freelance writer Greg Pedersen thinks Neil Giraldo is aces because he plays

BC Rich guitars and always shares his beer.